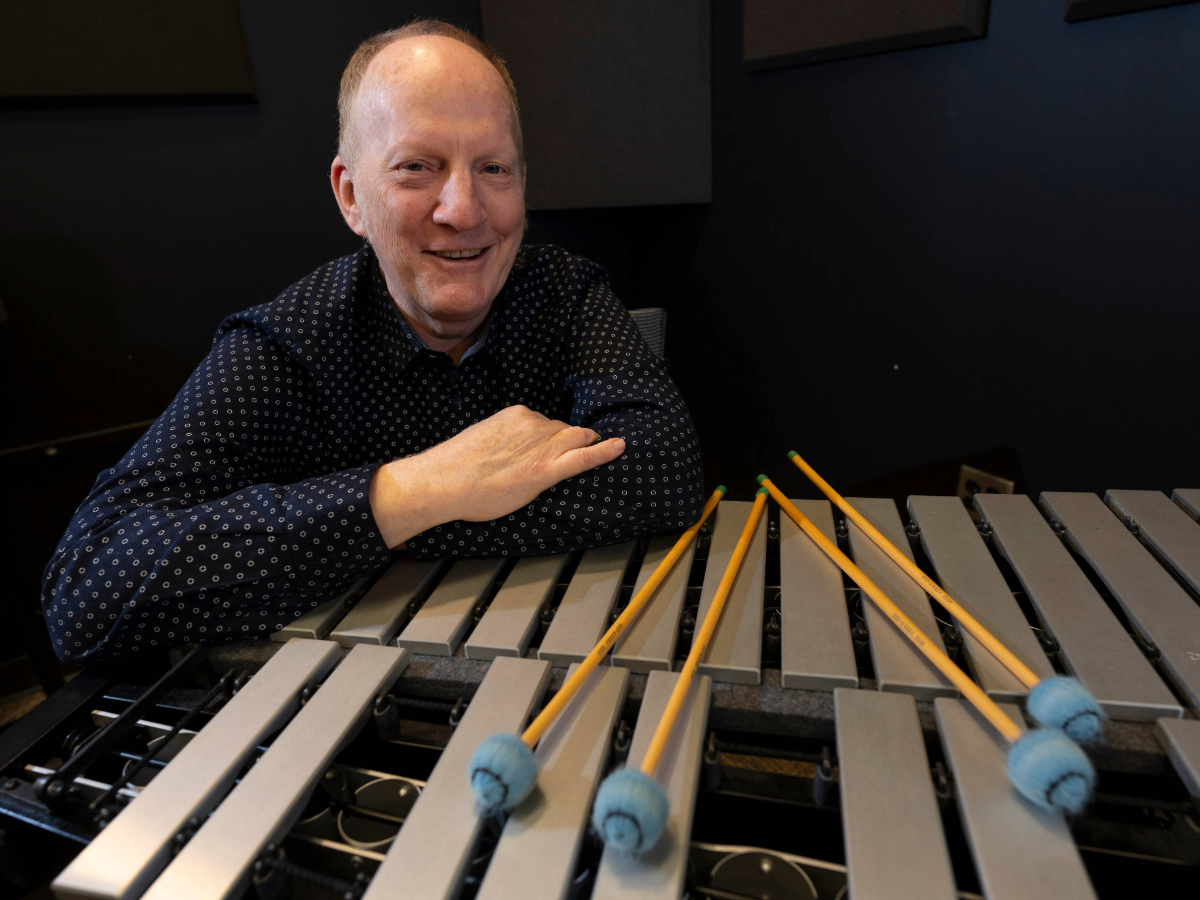

The integration of technological innovation with powerful performances is central to Professor of Music Technology Scott Deal's impressive career. However, he explains that cultivating relationships with friends, family, and colleagues has been just as important to his life and work. During his talk for the 2024 Last Lecture Series on November 8 at 2 p.m. in the Campus Center's Lower Level Theater, Deal will reflect on the impactful people, conversations, and experiences that have shaped his 33-year career. In this candid conversation, Deal gives us a sneak peek into his lecture and shares some thoughts on art, relationships, and the importance of "living with the end in mind."

HERRON: How would you describe the work you do?

SCOTT DEAL: It's all about computer interactivity and music performance, in many phases and in many forms. If there's a computer involved and musicians playing instruments, then it is something I would be interested in.

HERRON: When you say "if there's a computer involved," you're not just talking about digital music, right? Do you mean artificial intelligence is involved in your music?

SCOTT DEAL: That definitely includes artificial intelligence. More broadly, I would call what I do "interactive computational processes involving musical performance." For instance, something I've been working with for a very long time is telematics. Telematics is all about putting performers together that are separated by distance over the internet and combining media, live performers, content, information, and fixed media.

A lot of my work has been using the computer as a portal to a world where suddenly any space is a performance space and no one's limited by distance and you can have multiple audiences.

HERRON: Post-2020, virtual meetings and virtual performances are more commonplace. When you started doing telematics, it probably wasn't as familiar, right?

SCOTT DEAL: I started doing this kind of work in 2003 at the University of Alaska. The kind of bandwidth we all enjoy in our house now was considered research-grade bandwidth in 2003, available only to select universities who could afford it and even then, the use of it was heavily controlled.

The University of Alaska is a research university, and they wanted to get going on internet research, so they approached me for collaboration because I was a percussion professor who also happened be doing all this crazy electronic stuff and doing things with technology. They told me, "There's a group of artists across the United States that are working together on stuff like you."

I teamed up with them through the UAF Supercomputing Center, which was well-funded, so I got whatever I needed to do this research. It was a dream come true, and much more fun for me than being a traditional musician. So what I started working on was a kind of interactivity where I'm here and there's a screen with other people on the other side. I'm doing processes or playing, and then someone on the other end is getting my audio signal and they're processing it with their computer to make crazy electronic sounds and create interesting visual media.

After I came to IUPUI [now IU Indianapolis], I worked with a researcher named Ben Smith and we developed some difficult to use (but really interesting) machine learning systems. He was the coder, and I was the musician. I couldn't program something if my life depended on it and I told the department that when they hired me. So I collaborate with the coders and the programmers, because often they can't do what I do, which is to create original musical content and perform it in front of live audiences. It's always a team effort, an interdisciplinary effort.

Lately I've been working with Jason Palamara who's also a professor in Herron's music technology department. He's developed this really amazing app called AVATAR. I play the vibraphone and the app listens to the vibraphone. That's actually a big development because it used to be that you just in-putted MIDI, which is a music language for computers. It's not recording, it's not the sound, it's just replaying the language. Now computers are fast and sophisticated enough that they can listen to real audio and pick out the notes that I'm playing. The app can play with me, which is mind-blowing.

Jason is the coder and he puts the software together and builds it and then we get together and install it on my computer and then I take it and I work with it. I practice endlessly and try things out and try to make some art with it. Then we get back together and I report about what works and what doesn't. So that's how we've developed it: I'm the user and the beta person and then we write papers together.